There was a collective sigh of despair when Australia’s national electric vehicles strategy was finally released last week.

Around the world, governments and carmakers are phasing out petrol cars. Britain will ban new sales of petrol and diesel cars by 2030.

US President Joe Biden plans to use rebates and incentives to get Americans to switch to electric vehicles as part of his goal to reach net-zero emissions by 2035. General Motors in the US will stop selling petrol and diesel-powered cars by the same date.

But the Future Fuels Strategy handed down by Energy Minister Angus Taylor and Infrastructure Minister Michael McCormack offered only a vague vision: “Create the environment that enables consumer choice, stimulates industry development and reduces emissions.”

The ministers said Australia would continue to use a mix of vehicle technologies and fuels in the future, saying they wanted to support a “natural uptake” of electric cars rather than trying to “force people out of the cars they love”.

Given that Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who still has not committed Australia to a date for net-zero emissions (with 2050 the earliest likely date if he does,) said in 2019 that electric vehicle targets would “end the weekend”, no one really expected the government’s discussion paper to be revolutionary.

But the electric vehicle industry and motorists associations are unhappy that the government is not even considering the most basic incentives, such as tax breaks, to get more people buying electric cars.

Electric Vehicle Council chief executive Behyad Jafari is frustrated that the government doesn’t seem to have any plan for getting electric vehicles from less than 1 per cent of vehicles sold in Australia to at least 5 per cent. “That’s the key part they’re trying to skip,” Mr Jafari said.

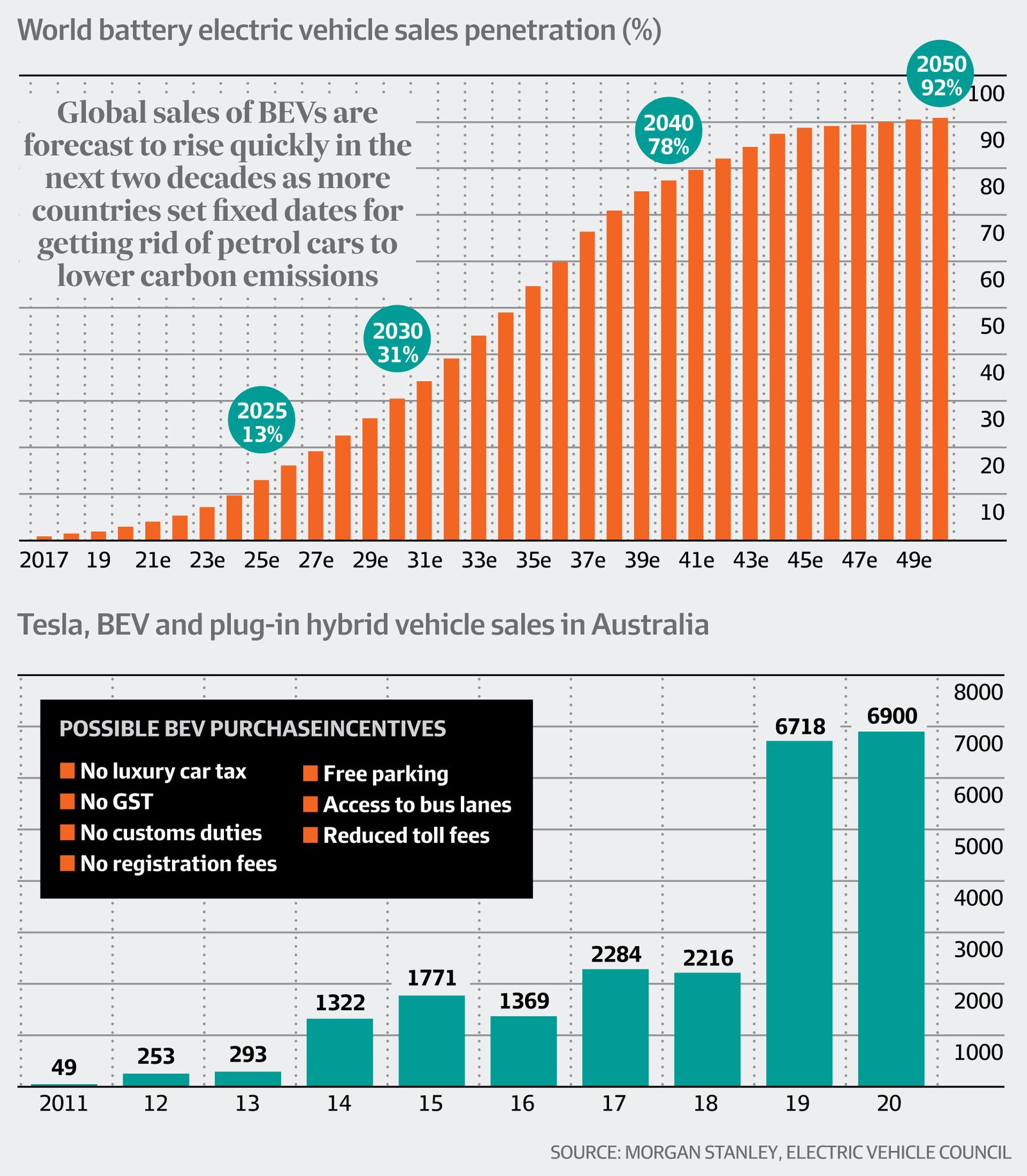

Australian sales of electric vehicles, including plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (which have bigger battery packs than regular hybrids which still rely mostly on fossil fuels for power) and Teslas in 2020 numbered 6900, just 0.75 per cent of car sales and a tiny increase on the 6718 vehicles sold the previous year.

Meanwhile in Europe, sales are soaring in countries that provide incentives and tax breaks. In France, battery electric car sales are averaging almost 10,000 a month and now have a 6 per cent penetration of the broader car market, according to Morgan Stanley. In Norway, battery electric car sales are now 54 per cent of new car sales.

Morgan Stanley has forecast that electric vehicles will account for almost one-third of global car sales by 2030, driven by countries setting hard emission reduction targets.

Car manufacturers contacted by The Australian Financial Review were reluctant to comment on the record, fearful of a political backlash.

But they said the countries that gave consumers incentives to buy electric cars would get them first. “It’s a simple matter of directing vehicles to markets where the sales are the highest,” said one automaker.

In Germany, not only are consumers offered financial incentives of €9000 ($14,070) to buy electric cars priced under €40,000, which has allowed some manufacturers to offer leases on electric cars for less than $100 every month or even for free but gas-guzzling sports utility vehicles are taxed at higher rates.

In addition, manufacturers are fined if they don’t hit European emission reduction targets.

Automakers also believe the strategy paper’s focus on regular hybrid cars as “a natural choice” for consumers after petrol cars is backward, pointing out that while hybrids reduce carbon emissions, they don’t actually lead to zero emissions.

“Hybrid vehicles are considered to be yesterday’s technology,” one manufacturer said.

Will Golsby, the general manager of corporate affairs at West Australian motorists’ group RAC, said the organisation was pleased with the strategy paper’s focus on developing a bigger national network of vehicle chargers and encouraging business and government fleets to switch to more fuel-efficient vehicles. The government hopes electric fleet vehicles will appear on the second-hand market, helping to lower prices.

“But it’s disappointing no targets are proposed,” Golsby said. “We’re concerned neither this paper nor the WA State Electric Vehicle Strategy has considered effective policy levers being used elsewhere, such as direct incentives and subsidies.

Technology and market dynamics alone will not deliver the changes we need to accelerate our transition to cleaner energy

— Will Golsby, head of corporate affairs at the RAC

“While moving in the right direction, technology and market dynamics alone will not deliver the changes we need to accelerate our transition to cleaner energy,” Golsby said. “It is critical governments at all levels complement these trends through proactive policy.”

The RAC wants to see tax breaks and exemptions for electric vehicles, subsidies on purchases and even options like parking discounts to be explored.

It says a recent survey of almost 500 members found more than 70 per cent wanted the government to do more to reduce vehicle emissions. Incentives and emissions standards for new vehicles were top of the list.

It claims around one in two members would consider buying an electric or hybrid car for their next vehicle and wants rating systems introduced to give car buyers more information on emissions and fuel consumption.

Jake Whitehead, a research fellow specialising in electric vehicle policy at the University of Queensland, says one of the main barriers to convincing drivers to switch to electric vehicles is the availability of vehicles that suit their households at affordable prices.

If the federal government offered incentives to electric vehicle buyers worth around $5000 (which could be in the form of tax breaks) to buy an electric vehicle, it could then charge them to use the roads to compensate for the loss in income derived from petrol taxes, he said.

Some state governments’ plans to introduce road user charges without first providing incentives have generated a backlash from the electric vehicle industry, which says the fees will make the vehicles even less appealing to buy.

The cheapest electric car on the market in Australia is the 2021 MG ZS EV, which retails for $43,990. Britain has 32 electric vehicles priced between $30,000 and $60,000 but Australia has just four, according to Jafari.

Sub-$50,000 target

“When someone is looking for a car, they are saying ‘show me a car under $50,000’ and we want electric vehicles to show up under that filter,” Jafari said, adding that car manufacturers needed to sell between 3000 and 5000 of any model to justify shipping them to Australia.

Cars incur various taxes, including a luxury car tax – which runs at 33 per cent for fuel-efficient cars worth $77,565 or more – as well as GST and customs duties.

The council also wants the government to set specific targets for phasing out petrol cars, such as those set by the NSW government for shifting to zero emissions buses.

Manufacturers are planning to start making hydrogen and electric buses in NSW from next year to meet the targets, boosting local employment. The Australian Trucking Association also wants incentives to encourage companies to buy zero-emission trucks and modernise Australia’s fleet (which has an average age of 12 years), including removing stamp duties.

Auto analysts, as well as manufacturers, acknowledge “range anxiety” remains an issue for many potential buyers of electric cars.

The distance electric vehicles can travel without needing to be recharged vary. Some are limited to about 250 kilometres but others are up to about 450 kilometres, and manufacturers say technologies will evolve to eventually allow the vehicles to travel up to 800 kilometres.

They also agree that more charging infrastructure is needed, particularly in country areas. Motorists associations have taken the lead in many states, including NSW, where the NRMA has installed 48 charging stations in 41 locations, of which all but one are outside Sydney.

Since December 2018, they have been used by 32,000 drivers. The three most popular locations, Sydney Olympic Park, Mittagong and Ewingsdale, near Byron Bay, are tapped into 100 times a month, according to the NRMA.

Super highway

Queensland claims to have the longest fast-charging network in a single state anywhere the world. It has 31 charging stations on the electric super highway from Coolangatta to Cairns, despite the state having only about 2500 electric vehicle owners.

Rebecca Michael, head of public policy for Queensland motorists’ association RACQ, says the super highway is popular but most of its members want to charge their cars at home.

However, members are worried that connecting cars to existing electricity grids that source power from fossil fuels undermines the vehicles’ environmental credentials, she says.

Dr Michael predicts electric vehicles will become more popular when people can develop home charging networks that draw power from solar panels and store energy in batteries.

She wants the federal government to outline exactly how Australia should shift to electric vehicles as part of a broader strategy to cut emissions. “Strong policy leadership is lacking,” she says.

Electrical vehicle manufacturers hope state and territory governments will pick up where the federal government has failed and take the initiative on introducing incentives. The ACT plans to scrap registration fees and provide interest-free loans to buyers of electric cars.

Whitehead hopes industry, motorists and state, territory and local governments will work collaboratively to “bring the federal government into the 21st century” and develop alternative strategies for decarbonising transport, which is one of Australia’s biggest sources of carbon emissions.

“We can’t on the one hand say we’re serious about achieving net zero by 2050 and then not have the policies in place to deal with transport,” Whitehead said.

“It all comes down to whether it’s just words, or whether we’re serious about putting in the action to back up those words.”

Extracted from AFR