China’s sabre-rattling about Taiwan underlines the need for Australia to be prepared for conflict in the South China Sea.

With its growing navy and air force, and the bases it has built throughout the area, China is increasingly capable of disrupting shipping lanes crucial to Australia’s exports and imports.

Of particular concern is our reliance on liquid fuels imported via South China Sea shipping routes. This reliance has become more pronounced over the past few decades as all but two local refineries have closed. So even while we export crude oil, we import about 90% of refined fuels.

Our research team was commissioned by the Department of Defence to analyse threats to Australia’s maritime supply chains throughout the Indo-Pacific region (the South China Sea and East China Sea).

We calculate a major conflict would threaten routes supplying 90% of refined fuel imports, coming from South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, Brunei and Vietnam.

Even if the routes between these countries and Australia do not pass through the South China Sea, most of the crude oil these countries import to produce that refined fuel does.

Previous analyses of vulnerability

It builds on broader analyses of supply-chain vulnerabilities, such as the Department of Energy and the Environment’s 2019 interim liquid fuel security review and the Productivity Commission’s 2021 report spurred by import shortages arising from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The 2019 liquid fuel security review determined that Australia imports the equivalent of 90% of its refined fuel needs.

In 2018 just five Asian nations supplied 87% of fuel imports: South Korea (27%), Singapore (26%), Japan (15%) and Malaysia (10%) and Taiwan (9%). The balance came from India (6%), the Middle East (1%) and the rest of the world including Vietnam and the Philippines (6%).

Shipping route vulnerabilities

Our analysis involved examining GPS traffic data for tanker and cargo ships throughout the South China Sea and East China Sea region.

It’s not just shipping routes between source countries and Australia that matter. It is where these countries import the crude oil they refine into petrol, diesel, jet fuel, marine fuel and kerosene.

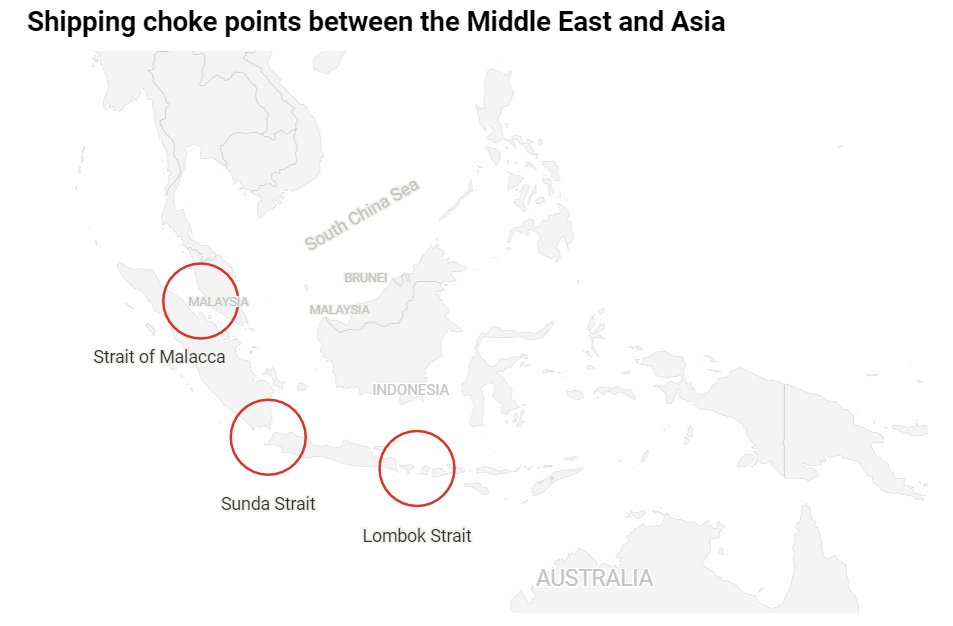

More than 80% of crude oil imports for Singapore, South Korea and Japan come from the Middle East – passing through the narrow Malacca Strait that separates the Malay Peninsula from the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

So, while export routes from Japan and Korea to Australia can avoid the South China Sea, their import routes can’t.

Any prolonged closure of the South China Sea will force tankers to take alternative routes. With longer routes will come higher freight costs and tanker shortages. Flow-on effects to Australia are inevitable.

Planning and preparedness

As the 2019 liquid fuel security review noted, Australia is a global outlier in its approach to liquid fuel security. Comparable economies manage fuel security as part of their strategic capability.

Australia by comparison, has chosen to apply minimal regulation or government intervention in pursuit of an efficient market that delivers fuel to Australians as cheaply as possible.

Until now, Australia’s strategic planning for conflict in the South China Sea has largely focused on military requirements.

With China’s increasing military capability and belligerence, there is no longer room to be complacent about Australia’s lack of energy security.

A 2019 workshop of engineering experts convened for the Department of Defence determined that Australia would run out of liquid fuels within two months of a major prolonged import disruption.

This would have cascading effect on all sectors of the economy – crippling transport, harming food security and emergency services. The experts warned that a lack of diesel for back-up generators in hospitals and other buildings could be catastrophic in the event of a large-scale electricity outage.

There are five main options to reduce our vulnerability:

1. Diversify import sources.

2. Increase local refining capability.

3. Reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

4. Increase strategic reserves.

5. Educate and prepare the population for possible shortages.

All will require government departments planning together with various industry sectors, including fuel retailers, refineries and import terminals, manufacturing, freight transport, maritime, defence, communities and other relevant stakeholders.

This article was was originally published in the Conversation. It was jointly written by Assoc Prof Richard Oloruntoba of Curtin University; Prof Booi Kam of RMIT University; Assoc Prof Hong-Oanh Nguyen of the University of Tasmania; Matthew Warren, director of the Centre for Cyber Security Research and Innovation at RMIT University; Prof Prem Chhetri of RMIT University; and Assoc Prof Vinh Thai of RMIT University.

Extracted from The Guardian