The heightened risk to Australia’s energy security from external shocks was starkly illuminated by the September 14 missile and drone attack on two of Saudi Arabia’s key oil installations, halving the kingdom’s oil output and reducing global oil supplies by almost 6 per cent.

This represents the biggest single outage the oil industry has experienced. Saudi output may not recover for months and no other country can compensate for the loss of 5.7 million barrels of oil a day or has remotely comparable spare capacity. The attacks have exposed the fragility of the whole global oil supply chain and there may be worse to come if tensions in the Persian Gulf escalate, with follow-up attacks a real possibility.

Despite our claim to be an emerging energy superpower, Australia is more vulnerable to disruptions to the flow of oil from the Middle East than almost any other developed economy. We depend on the Middle East for 40 per cent of our oil. But the bigger problem is the government’s failure to establish a strategic fuel reserve and our reliance on the market to manage oil supply volatility.

There are about 50 days of oil and fuel stored at refineries around the country, just more than half the recommended level of 90 days of net imports set by the International Energy Agency, which makes us non-compliant with our membership obligations.

When broken down, the shortfall is even more concerning. In the past 12 months the country had only 23 consumption days of petroleum in stock, 25 days of aviation fuel and 20 days of diesel. On any given day stocks can fall well below these averaged figures.

Australia is an outlier in being the only IEA member that does not maintain government-controlled stocks of crude oil or refined petroleum products above the recommended IEA level. Without a strategic reserve, we are completely reliant on the goodwill of our neighbours to supply us with fuel in an emergency caused by geopolitical tensions in the Middle East or Asia.

New world disorder

A market-driven approach may have served us well in the past. But, in an era often characterised as the “new world disorder”, energy policy must take greater account of national security considerations.

This is a government responsibility and cannot be outsourced to the oil companies or left to the vagaries of markets. Governments must lead in building a more resilient energy system that can future-proof the country from serious disruptions to the supply of oil, particularly liquid fuel, which accounts for half our energy consumption. Derived from crude oil, liquid fuel is refined into four main products: petrol, diesel, jet fuel and biofuels. They are the arteries of the Australian economy enabling every aspect of daily life, from the cars we use to do the grocery shopping and pick up the kids to the aircraft that fly us to our holiday and business destinations.

The transport sector is the biggest user of fuel, making up 75 per cent of total liquid fuel demand. Less known is the critical role of liquid fuels in sustaining the other foundational systems of our society. Mining and agriculture are more than 90 per cent reliant on diesel, and demand for diesel is growing much faster than the economy at 6 per cent a year.

Diesel shortfalls would translate quickly into food and resource shortages, illustrating the likely flow-on effects of an extended disruption to liquid fuel supplies. Diesel also provides emergency back-up for many of our essential services including water, sanitation and electricity.

Petrochemicals refined from crude oil and condensates are important, too. They are used in manufacturing for everything from plastics to makeup and super glue. In fact, we use three times more energy from liquid fuel than electricity. Our annual spending on liquid fuel is $57bn compared with $38bn on electricity and $37bn on gas. Stressed consumers anxious about their rising electricity bills would have much more to worry about if disruptions to oil supplies were to last more than a few weeks.

The bad news is that our liquid fuel resilience has deteriorated markedly in the past 20 years because of falling oil production, rising fuel imports, diminishing refining capacity, the absence of buffer stocks and complacency brought on by 40 years without a major disruption to oil supplies.

According to the Department of the Environment and Energy’s April interim report on the nation’s liquid fuel security, Australia’s oil production is 59 per cent lower than its 2000 peak and 75 per cent is exported. Forecasts show that oil production will continue to decline unless new reserves are discovered. What oil we do have cannot meet demand. As the gap between demand and supply has widened we have had to import increasing amounts of crude oil and refined products.

In recent years our oil dependence has become worryingly high. About 90 per cent of the fuel we use comes from oil sourced from overseas and 60 per cent of refined liquid fuel is imported. It’s misleading to claim our fuel oil resilience has improved because our sources of crude and refined product are more diverse. It’s true we import crude from 40 countries and refined product from 66 countries compared with 23 and 50 countries 20 years ago. But more than 40 per cent of liquid fuel sold here is derived from crude oil produced in the Middle East. And although most of our imported liquid fuel comes from Asian refineries in Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Malaysia and China, these refineries also receive most of their crude oil from the Middle East.

Compounding the problem is the marked deterioration in our capacity to refine oil domestically. A decade ago we had seven refineries; now we have only four — two in Victoria (ExxonMobil and Viva), one in Western Australia (BP) and one in Queensland (Caltex). This means the capacity to manage “short-term surge production and fuel switching” is significantly limited, a deficiency acknowledged by the Abbott government in 2015.

Moreover, the commercial viability of these remaining refineries is questionable as the transition away from fossil fuels to renewables gathers pace and the government commits to reducing by 2027 the sulphur content of Australia’s petrol, which is the highest among the 34 members of the benchmark OECD. Each of the four refineries will have to invest in the order of $250m to make them compliant. There is no guarantee the required investment will be forthcoming if decisions are based purely on commercial considerations. It is doubtful whether any new refineries will be built without government incentives because global demand for refined fuel is likely to peak in the 2030s.

Both Labor and Coalition governments have been slow to respond. The last two national energy security assessments were conducted in 2009 and 2011 when much higher levels of oil production and refining capacity made us far less vulnerable to supply disruptions than we are today. It was not until last year that the Turnbull government decided to launch a review of Australia’s fuel reserves following repeated warnings that the nation’s oil vulnerabilities were becoming serious.

Critics such as John Blackburn, a former deputy chief of air force, have long argued our national energy security assessments are outdated and that we lack a coherent energy policy. His arguments were given weight by a Senate inquiry in March last year into the security of critical infrastructure that found there were “supply chain vulnerabilities” in Australia’s fuel sector that needed remediation. Even the normally restrained IEA has expressed concern that Australia has become overly dependent on oil imports.

In announcing the Turnbull government review, Josh Frydenberg — then environment and energy minister — conceded Australia’s fuel reserves had fallen well below the IEA benchmark of 90 days’ supply. But he declared the government intended to exceed the requirement by 2026.

Sixteen months later the full review has yet to see the light of day. Energy Minister Angus Taylor seems to believe our lack of fuel reserves can be rectified by buying oil from the 645 million barrel US strategic petroleum reserve located in vast underground salt domes in Texas and Louisiana.

This idea has been slammed by critics such as Blackburn, who contend that even if Washington agrees to the request, having access to oil in the US is a poor substitute for having it bowser ready in Australia when our reserves are so low and could be expended before the oil arrives from the US. It would take a minimum of 30 to 40 days to get the oil here and refine it, a risky proposition given our reserves of diesel have fallen to as low as 12 days in recent years and sit at 22 days. There are also unanswered questions about who would refine the oil and how it would get here. The government has never guaranteed our four oil refineries will remain open. And Blackburn points out we have no Australian-flagged vessels capable of carrying the oil so we would be entirely dependent on the availability of foreign-owned ships.

Although the government professes to be relaxed about Australia’s capacity to manage oil disruptions, others are not so sanguine. Taylor argues that when supplies already on water are included, Australia’s commercially held stocks are close to 90 days.

Independent oil experts counter that the government’s willingness to include oil on ships and in foreign ports destined for Australia artificially inflates our fuel reserves and is contrary to the IEA’s reporting rules. Griffith University’s Liam Wagner says that in a conflict, or crisis, ships can be diverted or re-routed by the operator “even if that were against the law”. The Australian National University’s Llewelyn Hughes agrees that stock en route to Australia should not be included in our fuel reserves.

It’s abundantly clear that cost has been a major consideration in the reluctance of successive governments to establish a strategic fuel reserve. Building up stocks of liquid fuel and the infrastructure to store it safely would be expensive, requiring the investment of several billion dollars. But this must be weighed against the political, strategic and financial cost of a failure to provide a buffer for a critical resource at time when we have become too reliant on imported oil.

Those with an unbridled faith in the capacity of markets to smoothly and efficiently manage oil disruptions ought to reflect on this dependence and the destabilising impact of geopolitical rivalry. Oil companies operate a “just in time model” with limited reserve stocks. Although this makes commercial sense, it flies in the face of sensible national security policy during periods of geopolitical turbulence and uncertainty.

Expect to see further disruptions to oil supplies in the years ahead because Iran regards Saudi Arabia’s oil industry as the country’s achilles heel in the contest between the two states for regional supremacy. The airborne strikes on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq facility and the nearby Khurais oil field, which evaded Riyadh’s supposedly state-of-the-art air defence system, demonstrate how easy it is to damage vital oil installations and their associated infrastructure with relatively cheap drones and cruise missiles.

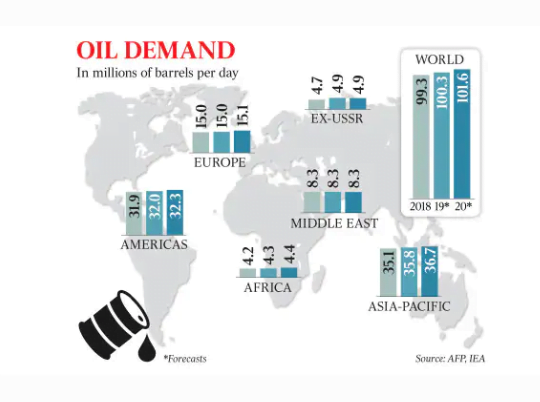

Even though the Middle East is not the force it once was in world oil markets, the region still produces one-third of global capacity and will remain a major source of oil for Australia. US shale oil cannot replace lost Saudi production. Washington’s new-found oil independence, courtesy of the booming US shale oil industry, has encouraged the Trump administration to take a hard line on sanctions against Iranian and Venezuelan oil exports. This has the perverse effect of putting a sanction’s premium on the cost of oil Australia buys on global markets.

Oil supplies also could be disrupted by conflicts closer to home as tensions between China and the US ramp up in the western Pacific and the long-running North Korean nuclear problem continues to simmer. Renewed ballistic missile testing by North Korea or an incident in the South China Sea involving US and Chinese ships or aircraft could quickly roil oil markets, sending prices higher. A more serious confrontation between the US and Chinese navies that led to a blockade of the Malacca Strait and disrupted imports of refined liquid fuel from Singapore and other Asian refineries cannot be ruled out.

Given the stakes, and the need for a comprehensive assessment of all the factors that are likely to impact on the price and availability of liquid fuel, Scott Morrison should insist that the Energy Minister add people with geopolitical expertise to the final liquid fuel security review panel as national security considerations ought to be central to the review’s deliberations and recommendations. Former ASIO director general David Irvine was drafted to the Foreign Investment Review Board when it became clear that decisions needed to be considered through a whole-of-government lens. The same thinking should inform the government’s approach to energy security assessments.

As argued by Resources Minister, Matt Canavan, boosting domestic oil production is the key to reducing our unhealthy dependence on imported oil. This means incentivising oil exploration and development in the Great Australian Bight, the Northern Territory’s Beetaloo Basin and offshore in the Timor Sea.

Establishing a government-controlled strategic fuel reserve and ensuring the necessary investment in our four remaining refineries must also be part of the solution along with improvements to the fragmented national oil monitoring system. Unlike the national electricity market, there is no national organisation with a holistic view of the liquid fuel sector. All of this will cost money, but it will be money well spent if the country can be protected from future oil shocks.

Finally, the government needs to think more deeply about the fuel requirements of the defence force. Under normal circumstances, ADF demand equates to 3 per cent of national demand for jet fuel and about 0.5 per cent of demand for diesel. But in a conflict these requirements could spike dramatically. There is no point in investing $100bn in expensive ships, aircraft and armoured vehicles across the next decade unless they have the fuel to get to their destinations. The ADF does not have strategic reserves of oil and is largely dependent on commercial stocks and infrastructure for the petrol, diesel and aviation fuel it needs. Any serious disruption to commercial supplies could bring the ADF to a grinding halt.

Extracted from The Australian